There have been murmurings of interest rate increases and with debt levels at their highest, the potential impact upon borrowers in their ability to make repayments could be devastating. There may be borrowers out there who will be squeezed as interest rates increase. But what is the real impact of interest rate movements and how likely are they to occur?

Australian Income and Spending capacity

Let’s start off with a quick bit of arithmetic. According to Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data cited by finder.com.au the average loan size in NSW is rounded up to the nearest thousand $726,000. This is always changing as more loans come to market. Moneysmart states that the average market interest rate is 2.32%. Through this calculation, the monthly repayment will amount to $2,811 at a 30-year term without fees. If interest rates moved just 25 basis points to 2.57%, the new monthly repayments become $2,905, a difference of $94. To a ten-year-old child, $94 is ‘all the money they could hope for’ where $94 to a millionaire may be a haircut. The point is that amount is relative to each person. Let’s bring this back to the type of people that could borrow $726,000 to provide some context.

If a couple earning the exact same income went to the CBA website and asks how much they could borrow. If they both earned a before-tax income of $50,600 with no dependents and monthly expenses of just $1,000 per month at a rate of 2.69%. They could borrow $725,500 If they went to ANZ. They were happy to lend $726,000 but required a more conservative before tax income of $65,850 each with the same data inputs.

This income is in line with ABS, NSW median income for 2021 ($50,153). If we have the difference of $94 then divide by 30 days multiplied by 7 days to make a week then divide the difference between two partners and that ends up to be $10.96 a week per partner. If the interest rate went up a full 1 percent then the weekly cost would be $45.15. In fact, for monthly repayments to double you would need an interest rate of 8.5615%. As we can see, small movements in interest rates do not adversely impact someone’s ability to make monthly payments nor alter their spending habits. It just might mean that they might have to skip that extra pint at the pub, or give up one night a week of takeaway food.

What makes interest rates move and how likely are they to?

This article could easily slide off onto a tangent about monetary policy, the International Money Market and all other kinds of influences on interest rates. As there are whole departments in banks and complex algorithms employed to decipher its inner workings. With the idea of brevity, I will try to keep these explanations succinct.

In basic form, the cash rate is the interest rate that commercial banks use to purchase or sell bonds in exchange for currency (cash) from the Reserve Bank (the price of money). By controlling the supply of cash, it manipulates the amount of money that a commercial bank could lend to borrowers. If there is not a lot of cash, the interest rate for borrowers will be higher and vice versa. The cash rate target is the amount set every first Tuesday of every month. If the cash rate is set higher, commercial banks will place those costs onto the borrowers and their interest rates will be higher. In theory, the cash rate can be set at any amount, but there are consequences to rash decisions.

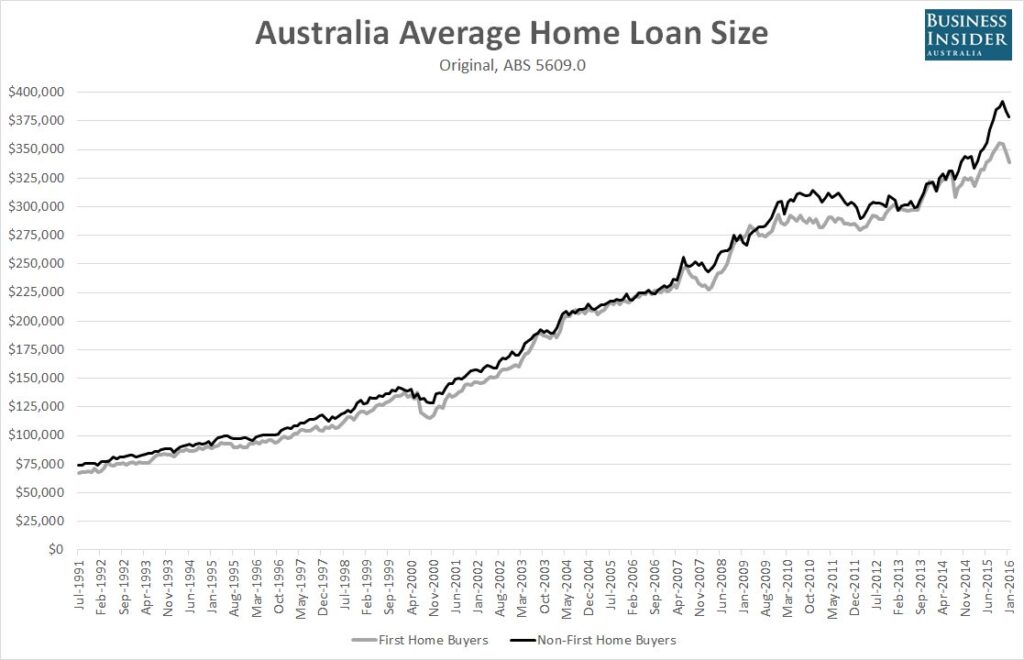

Historic Interest Rates and Debt

Historic data from the RBA shows that when the cash rate begins to increase (tightening) it tends to increase quite quickly. From July 1994 to December 1994, the cash rate increased from 4.75% to 7.5%. In October 1999 to August 2000, the cash rate increased from 4.75% to 6.25%. From December 2002 to February 2007, it moved from 4.25 to 7%. Finally, the last time it experienced an increase was from 3% in September 2009 to 4.75% in November 2010.

It’s important to note the context surrounding these rate hikes, especially during the 1990s. In the early 1990s interest rates dropped from an all time high in January 1990 of 17.5% down to 4.75%. Loan to value ratios were maxed at 80%. The deregulation of the banking system started. There was an influx of smaller loan providers into the market to compete with major banks.

If we take the year 1996. The average loan size was $100,070. At the same time interest rate stood at 10.25%. An ABS household income survey in 1996-97 states that household families were earning $890 per week. Annually $46,280 for the household or $23,140 each. This was a time when dual-income households were increasingly common. Mortgage terms were at 25 years. The monthly repayments were $943 per month based on the above data.

If we compare this example from the 1990s. Whereby the monthly loan repayment as a share of household income equated to 26.48% in 1996. With the example provided at the beginning of the article. We find that in today’s market the loan repayments to household income sit at 33.33%.

Inflation

According to the RBA, inflation in 1996 stood around 3.1%. Whereas today after the second quarter of 2021 inflation stands at 3.8% a sharp increase from the prior quarter. The Australian dollar bought 0.78 US Dollars in 1996 whereas today the US dollar buys 0.73 US Dollars.

When we compare the economic conditions that affect cash rate movements. We see that they are somewhat similar to the past and what happened in 1996. We can see that the debt burden as a portion of their income is similar to today’s borrowers. Could we infer that the implementation of monetary policy move in the same fashion as it did in the 1990s?

Interest Rates, the cash rate and their efficacy

There is a key concern for the cash rate as an effective instrument of monetary policy. As it loses efficacy at the extreme ends of the spectrums. When the cash rate is set so low at 0.1% and interest rates are 2.32% and if they move up to 2.57%. This is objectively still a cheap rate. Whereas when interest rates are at 16.75% and move down to 16.50%, that is still an expensive rate.

In 1996 with a cash rate of 10.25% there was plenty of room to move downward to improve overall spending and lower debt burdens, but at 0.1% there is very little room to move. With this in mind, only large movements in interest rates have any real effect in manipulating inflation and the supply of money. The Reserve Banks only option is to ‘tighten’ the economy and the only way it can do that is through a considerably large increase of the cash rate.

The increase of globalisation and the overlapping of economies have made each economy interdependent on one another. This coupled with technological advances in the speed and method that money is moved around has completely changed the nature of financial markets and economies globally. Reserve banks of OECD countries tend to follow each other’s movements in their cash rates unless going through severe economic trouble. When you talk about the US economy, the reserve bank of the United States is called the Federal Reserve and they very much dictate global cash rates as the US Dollar is considered a reserve currency and often used in payment for bonds in the international money market.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite the economic jargon what’s important to take from this is that. For interest rates to move, it would require most OECD nations to move cash rates in unison. Given the sensitivity of economies around the world due to the economic disruption caused by the pandemic, this is not likely to happen.

To even be effective in tightening the economy it would require a drastic increase in rates from a starting point where cash rates rarely venture (0.1%). If that were to occur, are you prepared for interest rates on your home loan to be at 5%? Each time interest rates on your home loan increase 25 basis points you lose a pint at the pub.

Alexander Gibson

Are your ready for any movement in interest rates?

Is your pre-approval holding you back from the home of your dreams?